Maryknoll nun helps New Mexico’s tribal peoples deal with uranium legacy

BY: MARK PATTISON

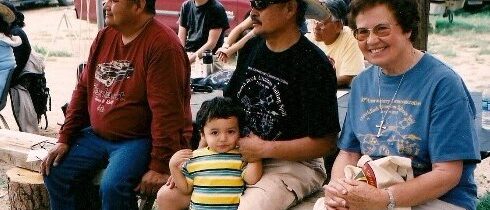

Maryknoll Sr. Rose Marie Cecchini is seen in Church Rock, New Mexico, at the annual commemoration of the July 16, 1979, radioactive spill in this undated photo. (CNS/Maryknoll Sisters)

When she was assigned to New Mexico 26 years ago after spending 33 years ministering in Asia, Maryknoll Sr. Rose Marie Cecchini never expected to spend so much of her ministry — and for such a lengthy period — helping the state’s tribal peoples deal with the literal fallout of uranium mining.

But she was trained to listen. And when she got to the Land of Enchantment, she got an earful.

“When I came in to the diocese, I came with this realization that I had to learn so much, just as I had to learn about the peoples of Asia,” Cecchini said.

Beginning her work in the Office of Peace, Justice and Creation with Catholic Charities for the Diocese of Gallup, whose 55,000 square miles includes portions of Arizona, she held listening sessions. “It took three years to complete this,” she said.

That’s how Cecchini learned of the legacy of uranium mining in New Mexico.

“Uranium [mining] took off during the 1940s and ’50s, developing in the atomic bomb and the Cold War scenarios,” Cecchini told Catholic News Service in a Sept. 21 phone interview from Gallup. “New Mexico was the source for the half of the uranium.”

She said there was “irresponsible mining and milling, hundreds of mines with no remediation and cleaning, continuing to contaminate the soil, the air and the water. … The radiation-related diseases and the cancer — all of this came into my consciousness.”

Cecchini found a connection with her ministry in Asia.

“In Japan, I was very aware of the church’s response to A-bomb survivors. I was seeing this underside of the whole of the whole nuclear cycle,” she said. “That’s what brought me into relationships with Indigenous, environmental groups and organizations, and at the same time, similar-purpose groups, other Christian groups and organizations, being more aware of all these contemporary issues that we deal with.”

Cecchini works with New Mexico Interfaith Power and Light, whose executive director is Franciscan Sr. Joan Brown.

“This afternoon, for example, I will have a conversation with Gallup Solar, started 14 years ago,” she added. “We’re very concerned about the environmental challenges. About the fossil fuel industry and the nuclear industry assaulting the earth and its resources.”

She outlined examples of both the bad and the good.

The bad: “We have the largest methane gas cloud hovering over the Four Corners,” Cecchini said. “That is due to the oil and gas drilling and the lack of oversight of the release of methane that’s contributing to the climate crisis.”

The good: “New Mexico is one of the ideal locations — the second most ideal location in the U.S. — for solar energy. We wanted to focus especially on the realization that many of the Navajo — something like 14,000 households — have no access to electricity. They are miles from the nearest power line, and it costs $1,000 a mile to get a power line to your home.”

Slowly but surely, Cecchini and her many allies are chipping away at the lack of access to electrical power which hundreds of millions of Americans take for granted.

“We have a training program for the fifth year where we train 10 Native American men and women in the basics of solar energy. We have a 12-volt, 200-watt system,” she told CNS. “They are taught all the components and the power potentiality and safety measures and so forth.”

But during the pandemic, “we could not meet in person,” she noted.

Maryknoll Sr. Rose Marie Cecchini is seen in Church Rock, New Mexico, at the annual commemoration of the July 16, 1979, radioactive spill in this undated photo. (CNS photo/Maryknoll Sisters)

The 10 candidates chosen for the program each year “receive an iPad with all the lessons, basics in solar energy,” she said. “Every two weeks we have this phone conference call with the students to address their questions.”

“When they finish the curriculum sessions that they have one-on-one, they learn to wire the components together and they take the [solar] unit. And they identify whether they themselves will receive the system if they have no electricity or if they have a relative or friend who lives on the reservation and they will install it at their home,” Cecchini continued.

A solar tech oversees the candidate who is completing the program by installing the unit on a particular home in Navajo land, she said.

“They’re required to take photos and videos on what was installed and what was the experience like and how the family responds to it, and what appliances they have now that they didn’t have before.”

Cecchini says the Native people call it “energy sovereignty.”

Now 88, Cecchini said she thinks about her Maryknoll orientation “from the beginning.”

“I think it’s the willingness to go beyond borders, to have that heart of love, because we’re energized by God’s love which is flowing out through all creation and all people,” she said.

“By transversing the generated divisions and the racial boundaries, somehow, all that needs to be our terrain of mission. It keeps all of that as common to our vocation.”

Cecchini added, “When I came in ’96, there were about five Maryknoll sisters, so I’m the last of the Mohicans. But it’s been a glorious and wonderful gift. I can never thank God enough.”