Navajo community residents wary of ‘devastating’ plan to move uranium tailings nearby

Arlyssa D. Becenti, Arizona Republic | Feb 23, 2023

The Red Water Pond Road Community Association wasn’t surprised when the Nuclear Regulatory Commission decided to issue a license amendment allowing the United Nuclear Corporation to move toxic waste from the Northeast Church Rock mine to the company’s uranium mill site near Gallup.

Teracita Keyanna, who is from Red Water Pond Road and a member of its association, said she received word about the license amendment last week, but had known for a few weeks that the commission would go against community wishes and approve disposal of approximately 1 million cubic yards of mine waste not far from the Navajo Nation and the Red Water community.

“It’s been devastating for us as a community and we want to fight it,” said Keyanna. “But we were basically getting ready for that devastating news that it’s going to end up staying in the community. We’ve always said the same thing and that is we want the waste removed offsite. It’s frustrating for the community to continue to hear that’s not an option that they’re going to go with.”

The proposed license amendment allows UNC to transfer the uranium mine waste currently at the abandoned Northeast Church Rock uranium mine on the Navajo Nation and dispose of it on top of the neighboring uranium mill tailings impoundment at the UNC Church Rock Mill Site, which sits about a mile outside Navajo Nation boundaries.

The mine waste would be excavated from the Church Rock Mine site and placed in a repository to be constructed on top of the existing mill tailings impoundment at the mill site. The amendment also revises the NRC-approved tailings reclamation plan and reclamation schedule for the mill site, according to the NRC’s record of decision.

Moving the toxins a mile down from the Navajo Nation to the mill site would be cheaper, according to a discussion of the plan in a 2021 radio forum. Moving the waste to the mill site would cost about $44 million, according to the 2021 reports, while disposing of it at the nearest off-reservation facility would cost about $293 million.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency will next begin work on a proposed consent decree that would provide UNC with direction on how to move forward. The EPA and the Justice Department will negotiate with responsible parties and, if agreement is reached, will produce a proposed consent decree for public review and comment.

After consideration of all public comments, a federal district court will decide whether to enter the consent decree as a final order. If it does, UNC will begin the cleanup.

Without an agreement, the EPA has other enforcement options to require cleanup to proceed. The Church Rock facility is a designated EPA Superfund site.

Environmental damage:Navajo residents say they won’t let the government forget about poisoned uranium mines

Community still feels effects of historic waste spill

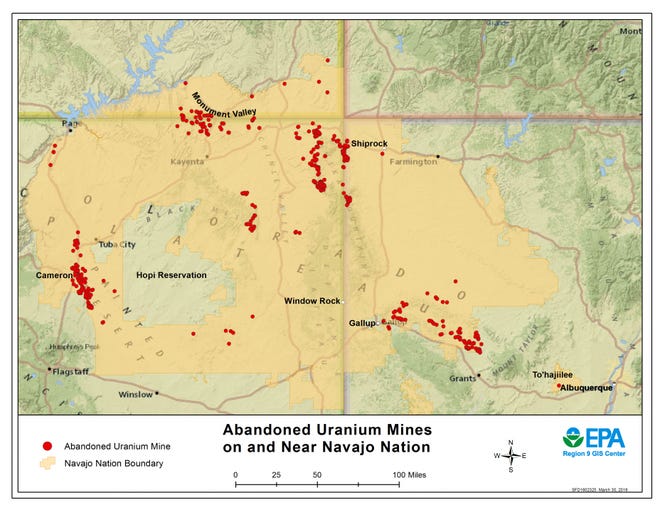

After extensive mineral exploration in the 1950s and 1960s, uranium mining began at the Church Rock Mine Site in 1967 and ended in 1982, according to the EPA. While the mine operated, it served as the principal mineral source for the UNC uranium mill.

Red Water Pond Road Community sits about 20 miles northeast of Gallup, and is near the site of an unprecedented tailings breach in July 1979, when a holding pond at the Church Rock uranium mill released about 94 million gallons of radioactive tailings into the Puerco River. The breach affected 11 Navajo communities along, with the Red Water Pond Road Community, and is still the largest release of radioactive material in U.S. history.

“The embankment of the tailings impoundment was then repaired,” said Ashley Waldron, environmental project manager for the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission in the 2021 radio forum. “The spill was cleaned up and corrective actions were taken.”

Following the tailings spill and related corrective actions, UNC resumed uranium milling operations, and eventually disposed of an estimated 3.2 million metric tons of tailings at the UNC mill site.

Navajo Nation lands surround the proposed project area, and nearby Navajo communities have disproportionately borne the environmental and health effects of nearby uranium mining and milling over many decades, said Christopher M. Regan, director of the NRC’s Division of Rulemaking, Environmental and Financial Support, on the NRC’s record of decision for the amendment.

“Some of the major concerns raised by Navajo people, government or organizations were related to water and soil contamination from past mining and milling activities, people’s health and the health of their livestock and other animals, the length of time required to identify a cleanup action, moving the waste to a nearby site instead of farther away, appropriate communication and dialog with the Navajo people, and numerous specific aspects of the proposal,” he wrote.

Mining legacy:Parents want a decision about plans to replace a Navajo school near old uranium mines

Tainted water forced school shutdown

The Navajo Nation has endured often disastrous consequences from decades of mining and the historic waste spill. But Keyanna and her community say they are tired of waiting to see if the federal government will actually do anything for the betterment of the land and people. She said she refers to what’s happening as “No government activity. Just radioactivity.”

One of the many consequences of the spill was discovered only in 2015, when Navajo researcher Tommy Rock, who was testing unregulated wells along the Puerco River, measured uranium levels at 43 parts per billion in the water in Sanders. That’s well above the EPA limit of 30 parts per billion.

“The contaminated runoff from uranium mining has degraded the Puerco River and for decades has negatively impacted the people that rely on it,” said Rock in 2019 in testimony before a U.S. House Natural Resources subcommittee.

Keyanna said when the contaminated water was found in Sanders, the school had to shut down for a while and bottled water was brought in. Following the discovery, Navajo Tribal Utility Authority bought the Arizona Windsong Water Company, a public water system that served the Park Estates in Sanders.

Wells serving the former Arizona Windsong water system were taken offline so NTUA could serve the community. A treatment plant to remove uranium went online in 2017 at the Sanders Unified Elementary School to treat the water there.

“For Sanders, it was the 1979 spill that caused uranium contamination to get into their water table,” said Keyanna. “That happened in the 70s. Why has it taken nearly 50 years for any action?”

‘They’re being ignored’

Rock, who is currently a Princeton University Presidential Postdoctoral Research Fellow, said his research at that point was in collaboration with grassroots efforts from the community as well as with the nonprofit Tolani Lake Enterprises. He was able to fund the work through an EPA environmental justice grant.

“It was a project that had to do with past mining activities downstream from Church Rock,” Rock told The Republic. “We wanted to know what the water quality was like. In order to do a lot of the water sampling I had to train people from the area.”

Keyanna and Rock, who is originally from Monument Valley, are two community members who have been affected by uranium mining and have taken it upon themselves to bring attention to the legacy of nearly 40 years of mining on the Navajo Nation. Rock is continuing research at Princeton related to his past studies of the water in Sanders.

“There’s a lot more that needs to be done in that area,” said Rock. “Sanders is a small community, and everyone knows one another and they would talk about their neighbors, family, or themselves having cancer or talking about cancer survivors. It’s a small community, to see that amount of cancer is surprising. They’re being ignored.”

The momentum kicked into gear on this license amendment at the beginning of the pandemic. The NRC had placed public meeting notices in local newspapers and in advance of each of the meetings, announcements were posted on the NRC public meeting notification system website. Public meeting announcements were also aired daily on radio station KTNN-AM 660.

The NRC received approximately 432 unique comments collected in 11 pieces of comment correspondence and two transcripts.

Former Navajo Nation President Jonathan Nez wrote his own letter opposing the amendment. He told John R. Tappert, former director of the NRC’s Division of Rulemaking, Environmental, and Financial Support Office, that the Red Water Pond Road Community and many other Navajo communities had been severely affected by the legacy of uranium mining on the Navajo Nation. Nez also met with NRC and EPA officials.

The Environmental Impact Study found that there were serious impacts to groundwater, public and occupational health, and historic and cultural resources from past uranium activities at the Church Rock mine and UNC mill site, according to Nez’s 2021 letter.

“Clearly the radioactive mine waste left abandoned at the NECR site must be removed,” Nez wrote. “Leaving it in place would have ‘large’ health and environmental impacts. Even removal of the waste will have ‘disproportionately high and adverse environmental impacts’ on nearby Navajo communities, due to transportation-related effects, impacts to air quality, increased noise levels, and visual disturbances.”

Although Nez tried to support the community’s wishes, Keyanna said the lack of Navajo leadership helping her community is frustrating. She said getting an advocate from Navajo leadership, whether delegates or the president, has yet to happen, and although she understands there are other pressing matters, it doesn’t change the fact that this specific issue needs addressing.

“There’s no one being a champion for us,” said Keyanna. “We need all our council delegates to be champions for the community itself. They’re not doing that. It’s their job but they’re not listening to the people who got them into those positions.”

New uranium mining on the Navajo Nation isn’t too far-fetched, activists say, and the idea that Navajo leadership would allow it is a concern. Before Nez left office, he vetoed a bill that the council passed, in spite of community opposition, to allow Navajo Oil and Gas to explore for helium in two Navajo communities. So far, the new Buu Nygren-Richelle Montoya administration has not taken a clear position on such exploration or extraction.

“When it comes to natural resource extraction our leaders are not well informed of the consequences to natural resource extraction,” said Rock. “You can look at Peabody and what happened there, and uranium, and oil and gas as well.”

Arlyssa Becenti covers Indigenous affairs for The Arizona Republic and azcentral. Send ideas and tips to arlyssa.becenti@arizonarepublic.com.